In an era of high tech, cutting edge, inheritable, nucleic acid editing, I am infinitely surprised that not less than five people within the last three weeks have described to me their studies on parasite prevalence, in which they used certain morphological criteria to definitively distinguish between, and identify two or more closely related species that have similar morphologies, using an atlas or a picture that they found online using Dr. Google.

Here is an analogy. Imagine the existence of an intelligent alien race, that has a picture of me in its "Atlas of sentient life forms", in which I am wearing a blue sparkling headband, blue shirt, white shoes and a white labcoat. The description underneath says, "Veterinarius parasitologistius - adult. Identification: Anterior part of body (known as "head" in the parlance of the organism) covered with numerous strands of black keratin, attached to which is a thin blue sparkling band. Two thin fore limbs seen, along with two hindlimbs which are capped in white, using which the organism is attached to the surface of the planet and which it uses for motility. The organism has a white outer layer, under which is found a blue layer. We are yet to ascertain which of these layers is the actual cuticle. The organism is uncommon, and is only found on the third planet orbiting the star Sol, in the Orion Arm of the spiral galaxy Milky Way." Now, if a new alien were to find you and use you as a sample in its study titled "Diversity of life in the planets that orbit Sol", and if it were to compare your picture to its type-specimen picture (me), what will its conclusion be? Will it record that since the new specimen has keratin of a different color (assuming that your hair is not black) and cuticle that are not layers of white and blue (assuming that you are not wearing a blue shirt with a white labcoat), the new rare specimen appears to be a different species? In reality though, we are both humans (and you may well be a veterinary parasitologist as well). The differences between us are attributable to biological variation - features that we have inherited from our ancestors (genetics and epigenetics, if you will. But, we undeniably share over 99.99% of our genes - the ones that make us human).

One good thing about parasite morphology is that parasites of the same species are more clonal than human beings are. But, this clonality is not absolute. Biological variation is inherent because of the stochastic nature of meiotic crosses. But, given the complex lifecycles of parasites, different stages may not even resemble each other. Allow me to illustrate.

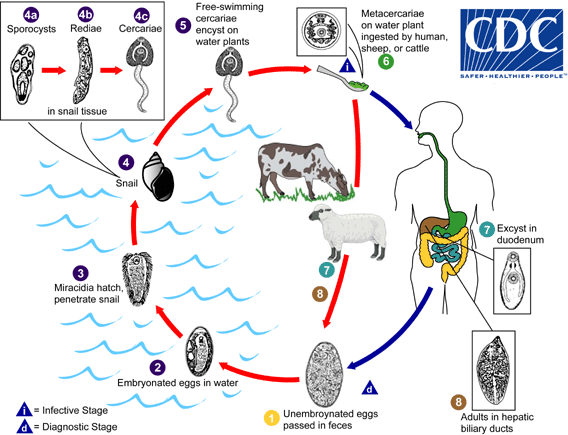

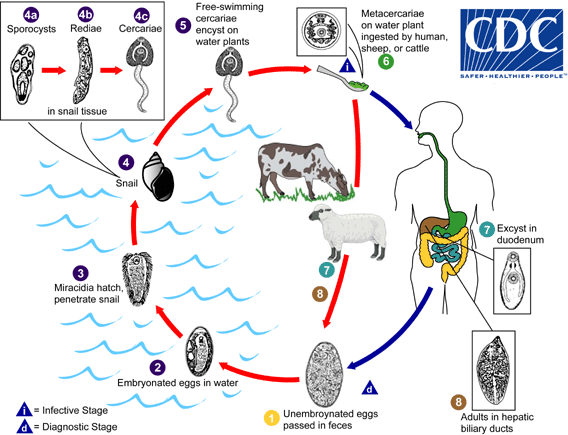

Adult liver flukes of the genus Fasciola have a characteristic leaf shape with an anterior oral sucker and a ventral sucker, and are found in the liver of ruminants and humans. The miracidium stage of the parasite looks nothing like the adult, because it is free living, covered with cilia and is "infectious" to snails. The cercaria even has a tail! But looks nothing like the adult or the miracidium. However, there is no denying that they are all the same species (Thomas, A.P., 1883). Suppose you sample water from a lake and find a miracidium, and suppose your atlas has no picture of a Fasciola miracidium, is it appropriate for you to name this parasite after yourself (which you can't technically do under the ICZN rules), and tweet #ifoundanewparasite?

Suppose alternatively that you have actually identified the miracidium as belonging to a trematode. How sure can you be that it is a miracidium of Fasciola and not the miracidium of Clonorchis or Dicrocoelium or Paragonimus? Are dichotomous keys based on overlapping length ranges enough for the identification?

The answer is no. You cannot definitively identify a miracidium without resorting to molecular techniques.

The lifecycle of Fasciola, which also shows the morphology of life cycle parasites. Source: CDC

For more pretty pictures of the lifecycle, see a recent article in the Korean Journal of Parasitology @ http://parasitol.kr/journal/view.php?number=1870

And then there is the case of sexual dimorphism. For example, female oxyurids are larger than male oxyurids (Morand, 1998). If you were to find only a juvenile male as a result of your collection efforts, would it be right to compare its length to that of a female adult and declare the discovery of a new species or even a genotype, not realizing that your specimen is in fact a male?

And the alternate scenario, in which you identify it as a male, but have no explanation for why it is shorter than adult males are supposed to be.

The existence of species that look alike, even if their behavior is different poses another challenge to morphological identification. In the case of pathogenic parasites like Trypanosoma, if a veterinarian relies solely on morphology to distinguish between pathogenic T.brucei brucei (which causes nagana in cattle), and non pathogenic T.theileri, he is doomed, and so is the animal that he is attempting to treat, as is its owner. You may argue that the vectors for the two parasites are different. Yes. That is true. But the last time I checked, Trypanosomes on bovine clinical blood smears don't wear name badges that say which intermediate host they like to use.

The most logical thing is for us to ask ourselves, and each other these questions:

So, how now shall we id? The next time you tell someone that you like to identify rare parasites of an equally rare wild host species <insert your favorite host species here>, using morphometerics, it behooves you to back up your claims with supporting molecular data.

It is incumbent upon you to understand your data before you share it.

As always, opinions expressed are my own, you may choose to share them or choose not to.

References :

Morand S., Hugot J.(1998) Sexual size dimorphism in parasitic oxyurid nematodes, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 64,3,397-410

Thomas, A.P. (1883) The life history of the liver-fluke (Fasciola hepatica).QuarterlyJournal of Microscopical Science 23, 99–133

So, you made it to the end of the post! Great! As a reward, here is the picture of the type - specimen that is found in the alien's book.

From the best seller "Atlas of sentient life forms", from the publishing house Messier83, year Magellanic 0.197M, a collaborative effort of the Redshift consortium, page Q1W2E3

Here is an analogy. Imagine the existence of an intelligent alien race, that has a picture of me in its "Atlas of sentient life forms", in which I am wearing a blue sparkling headband, blue shirt, white shoes and a white labcoat. The description underneath says, "Veterinarius parasitologistius - adult. Identification: Anterior part of body (known as "head" in the parlance of the organism) covered with numerous strands of black keratin, attached to which is a thin blue sparkling band. Two thin fore limbs seen, along with two hindlimbs which are capped in white, using which the organism is attached to the surface of the planet and which it uses for motility. The organism has a white outer layer, under which is found a blue layer. We are yet to ascertain which of these layers is the actual cuticle. The organism is uncommon, and is only found on the third planet orbiting the star Sol, in the Orion Arm of the spiral galaxy Milky Way." Now, if a new alien were to find you and use you as a sample in its study titled "Diversity of life in the planets that orbit Sol", and if it were to compare your picture to its type-specimen picture (me), what will its conclusion be? Will it record that since the new specimen has keratin of a different color (assuming that your hair is not black) and cuticle that are not layers of white and blue (assuming that you are not wearing a blue shirt with a white labcoat), the new rare specimen appears to be a different species? In reality though, we are both humans (and you may well be a veterinary parasitologist as well). The differences between us are attributable to biological variation - features that we have inherited from our ancestors (genetics and epigenetics, if you will. But, we undeniably share over 99.99% of our genes - the ones that make us human).

One good thing about parasite morphology is that parasites of the same species are more clonal than human beings are. But, this clonality is not absolute. Biological variation is inherent because of the stochastic nature of meiotic crosses. But, given the complex lifecycles of parasites, different stages may not even resemble each other. Allow me to illustrate.

Adult liver flukes of the genus Fasciola have a characteristic leaf shape with an anterior oral sucker and a ventral sucker, and are found in the liver of ruminants and humans. The miracidium stage of the parasite looks nothing like the adult, because it is free living, covered with cilia and is "infectious" to snails. The cercaria even has a tail! But looks nothing like the adult or the miracidium. However, there is no denying that they are all the same species (Thomas, A.P., 1883). Suppose you sample water from a lake and find a miracidium, and suppose your atlas has no picture of a Fasciola miracidium, is it appropriate for you to name this parasite after yourself (which you can't technically do under the ICZN rules), and tweet #ifoundanewparasite?

Suppose alternatively that you have actually identified the miracidium as belonging to a trematode. How sure can you be that it is a miracidium of Fasciola and not the miracidium of Clonorchis or Dicrocoelium or Paragonimus? Are dichotomous keys based on overlapping length ranges enough for the identification?

The answer is no. You cannot definitively identify a miracidium without resorting to molecular techniques.

The lifecycle of Fasciola, which also shows the morphology of life cycle parasites. Source: CDC

For more pretty pictures of the lifecycle, see a recent article in the Korean Journal of Parasitology @ http://parasitol.kr/journal/view.php?number=1870

And then there is the case of sexual dimorphism. For example, female oxyurids are larger than male oxyurids (Morand, 1998). If you were to find only a juvenile male as a result of your collection efforts, would it be right to compare its length to that of a female adult and declare the discovery of a new species or even a genotype, not realizing that your specimen is in fact a male?

And the alternate scenario, in which you identify it as a male, but have no explanation for why it is shorter than adult males are supposed to be.

The existence of species that look alike, even if their behavior is different poses another challenge to morphological identification. In the case of pathogenic parasites like Trypanosoma, if a veterinarian relies solely on morphology to distinguish between pathogenic T.brucei brucei (which causes nagana in cattle), and non pathogenic T.theileri, he is doomed, and so is the animal that he is attempting to treat, as is its owner. You may argue that the vectors for the two parasites are different. Yes. That is true. But the last time I checked, Trypanosomes on bovine clinical blood smears don't wear name badges that say which intermediate host they like to use.

The most logical thing is for us to ask ourselves, and each other these questions:

- How much should we rely on morphology to identify a rare parasite?

- If a parasite has been described only once before, in a foreign language, should the claim be made that your new specimen is a new species, because of slightly different morphometrics?

- Is it correct to claim that you have identified a species using morphology, if you cannot produce photographs and reasons for the identification?

- Is it okay to use a non-comprehensive atlas published in 1980 for the purpose of field identification?

- Is it proper to not use microscopes in the field, because they are too heavy to lug around?

- And since you are deep freezing your samples instantly after collection, it is perfectly acceptable to identify the parasites using morphology, a month after your return from field work. Right?

So, how now shall we id? The next time you tell someone that you like to identify rare parasites of an equally rare wild host species <insert your favorite host species here>, using morphometerics, it behooves you to back up your claims with supporting molecular data.

It is incumbent upon you to understand your data before you share it.

As always, opinions expressed are my own, you may choose to share them or choose not to.

References :

Morand S., Hugot J.(1998) Sexual size dimorphism in parasitic oxyurid nematodes, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 64,3,397-410

Thomas, A.P. (1883) The life history of the liver-fluke (Fasciola hepatica).QuarterlyJournal of Microscopical Science 23, 99–133

So, you made it to the end of the post! Great! As a reward, here is the picture of the type - specimen that is found in the alien's book.

From the best seller "Atlas of sentient life forms", from the publishing house Messier83, year Magellanic 0.197M, a collaborative effort of the Redshift consortium, page Q1W2E3